The Commonwealth of Jerusalem

The Jerusalem Commonwealth

Building Bipartisan Cooperation while

Maintaining Self-Determination for Israel and Palestine

Rationale

This proposed model assumes that the

two state solution may never materialize, and instead proposes an alternative

solution: a political structure where self-governing territories for both

Palestinians and Israelis are empowered to fulfill their communities’ aspirations,

and where the two communities come together in a commonwealth system that

carefully and deliberately balances and shares power. The aim is to replace the current military

and sometimes violent sectarian conflict with a political system for sustained

conflict resolution and negotiation in a bipartisan commonwealth government

structured to promote cooperation and pursuing shared interests and mutual

benefits, without sacrificing security.

Key points in

summary

·

A commonwealth of

Israel and the West Bank with Jerusalem as the unifying and iconic capital city,

rather than as a symbol of division over which two rival states quarrel to make

it their own separate capitals.

·

A bicameral commonwealth

parliament with two chambers, the Hebrew Chamber and the Arabic Chamber. Citizens throughout the commonwealth can

stand for election or vote for candidates of either Chamber, but the role of

the Hebrew Chamber would be to promote and protect Jewish aspirations, and the

Arabic Chamber those of the Palestinians and Arab Israelis.

·

Legislation would

need the assent of both chambers to become law, so that bipartisanship would be

essential and inherent at the commonwealth level, and the parliament would tend

towards seeking shared interests and mutual benefits rather than extremist or

confrontational positions.

·

Giving both

chambers of parliament the right to veto legislation means that demographic

concerns of being out-numbered would have little importance, as the size of

each chamber does not affect the ability to veto. While deadlock is

possible, mechanisms can be found to break such deadlocks.

·

The executive would

not be led by a prime minister or president, but instead the executive would be

a directorate[1], seven

equal members of an Executive Council, members of parliament chosen by their

peers, which because of the demographic balance between Jewish and non-Jewish

communities, would be essentially bipartisan (likely to have four Jewish and

three Palestinian Councilors).

·

There would be territory

governments, each with its own unicameral assembly and executive, governing three

areas: Israel, the West Bank, and Jerusalem.

·

Addressing the enormous

problems existing in the Gaza Strip would be critical to the success of the commonwealth,

and Gaza would be developed as a dependent special territory associated but not

a full part of the Jerusalem Commonwealth until such time it can be admitted as

the fourth territory of the commonwealth, contingent on recognition of the

right of the Jewish people to a homeland in Israel.

·

Unlike the two

state solution, a commonwealth means freedom of movement and residency for all citizens

across all three territories, allowing Jewish settlements to remain and

Palestinian refugees to return to Israel, but both in an agreed controlled

manner.

While most democracies have a

governing party or coalition and an opposition, this adversarial majority-rules governance would be counter-productive,

in that it would divide rather than unite and build peace between Israel and

Palestine. In contrast, in the unicameral territory parliaments, majority

rule would apply, so that territories governments can seek to advance their

people’s aspirations.

THE JERUSALEM COMMONWEALTH

IN DETAIL

The Lands of

the Jerusalem Commonwealth

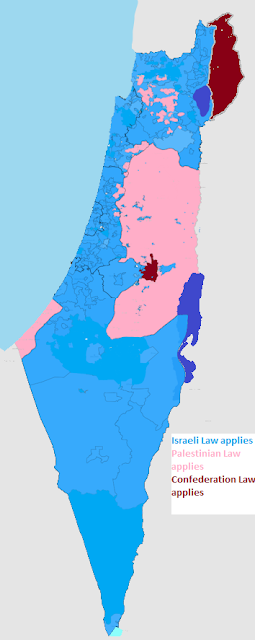

The

Jerusalem Commonwealth (‘the commonwealth’) would include the current territory of Israel and the West

Bank with the City of Jerusalem as its capital.

The Gaza Strip could be a dependent Territory

in formal association with the Commonwealth until such time it can be fully included. The Golan Heights could also be

included subject to negotiations.

Citizenship

All current Israeli citizens, long term residents of Israel and the

West Bank, and Palestinian refugees residing in

the West Bank would automatically become ‘founding’ citizens of the Commonwealth. Future rights to citizenship for new immigrants would be granted as set

out below. In this proposal, the term Palestinian will be

taken to include Arab Israelis, Druze, Bedouins and other non-Jewish communities indigenous to Palestine.

The Commonwealth

Territories

Territory of Israel

Based on the current six Israeli

administrative districts but without the metropolitan portion of the Israeli

district of Jerusalem.

The West Bank Territory of Palestine

Based on the 11 governorates of the

West Bank including Al-Quds but without the metropolitan portion in East

Jerusalem. The ‘Judea and Samaria Area’ would no longer exist as an administrative unit, and West Bank Jewish

settlements would be a part of this territory.

Capital Territory of Jerusalem

Jerusalem City, including both West

and East Jerusalem, but not including the remaining non-metropolitan portions

of the current Israeli district of Jerusalem and the Palestinian governorate of

Al-Quds. It would not only be the

Commonwealth capital, but also the location of both Israel and West Bank territorial

assemblies and governments.

Gaza Special Territory of Palestine

Initially, the Gaza Strip would be a

dependent territory of the commonwealth, the Gaza Special Territory, capital in

Gaza City. The people of Gaza would have

autonomy to run their own affairs, but not have representation in the Commonwealth

parliament. The IDF would manage its borders and maintain security. The territory would be eligible for full

membership of the commonwealth following a process of economic integration and

deradicalization, and recognition of the Territory of Israel as a Jewish

homeland.

Golan Heights and Land Swaps

Golan Heights would be returned to

Syria, unless otherwise agreed during peace negotiations including potentially

involving land swaps and following a plebiscite that supported annexation, as

either a commonwealth administered district or part of the Territory of Israel.

The territories would maintain

sovereignty over their territory borders but could negotiate internal land

swaps if mutually agreeable. However,

only the Commonwealth Government would have the power to negotiate land swaps

with Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon or Syria but such swaps would be subject to the

approval of the relevant Territory government.

Population of

the Commonwealth

The estimated populations of the four territories in 2020 are in table 1

below.

TERRITORY

|

TOTAL (000)

|

JEWISH

(000 and %)

|

PALESTINIAN

(000

and %)

|

ELECTED REPRESENTATIVES

|

ISRAEL

|

7570

|

5667 (74.9)

|

1903 (25.1)

|

151

|

WEST BANK

|

3173

|

418 (13.4)

|

2755 (86.6)

|

63

|

JERUSALEM

|

919

|

556 (60.6)

|

363 (39.4)

|

18

|

COMMONWEALTH TOTAL

|

11,662

|

6641 (56.9)

|

5021 (43.1)

|

232

|

GAZA

|

2048

|

0 (0)

|

2048 (100)

|

40

|

The population estimates are based on latest

official estimates for 2018 as at 19 September 2019 from the Central Bureaus

of Statistics, of Israel and

2020 projection from the Palestinian Bureau of Statistics released on 6 March 2020 as found at https://www.citypopulation.de/Asia.html .

Division of

Power between Territory and Commonwealth Governments

As far as possible, the functions of Government would remain mostly in

the domain of the territories, but certain powers would need to be ceded to the

Commonwealth Government as shown in table 2.

Table 2 : areas of

responsibility for Territory governments and the Commonwealth government

Territory

Government

|

Commonwealth

Government

|

Health,

Sport and Recreation

|

Defense

|

Education

and Research

|

Internal

Security and Justice

|

Social

Services, Child Care

|

Foreign

Affairs and Trade

|

Environment,

Water, Antiquities and Tourism

|

Immigration

and Citizenship

|

Planning, Housing,

Local Government

|

Taxation and

Economic policy

|

Territory

Law and Justice, Prisons

|

Commonwealth

Law (Attorney General)

|

Employment, Local

Transport, Road and Rail

|

Air transport,

Ports, Communication

|

Elected

Representatives

A national election would be held every four years to choose

parliamentary representatives. Elected

representatives would sit in the three unicameral territory assemblies according

to the electorates which they represent and in addition, the bicameral

commonwealth parliament. This dual parliamentary

role would minimize the risk of conflict between the commonwealth and territory

governments and engender a sense of unity of purpose. It would underline that the territories’

representatives are coming together in Jerusalem to form a joint commonwealth

government that serves both the Jewish and Palestinian peoples. Elected representatives thus are responsible

for decision making at both territory and commonwealth level.

Members of parliament would be elected

by proportional representation with one representative per 50,000 population. Based on the current populations, Israelis

would be entitled to 151 representatives, the West Bank Palestinians 63, and

citizens in Jerusalem 18, for a total of 232 elected representatives. Twenty-two electoral districts would be

created so that elected representatives would be more directly accountable at a

local level to the voters in their respective districts (table 3). Compulsory

voting by all adult citizens would ensure equality of representation across the

commonwealth.

notes on table 3:

1. Hebron: Hebron governorate but some northern areas included in the Central Palestine electorate

2. Central Palestine: Bethlehem, northern Hebron, and parts of Al-Quds east of Jerusalem toward the Dead Sea

|

3. Ramallah: Ramallah and portion of Al-Quds west of East Jerusalem and south of Ramallah

|

4. Jordan Valley: Jericho, Tubas and Jenin governorates

|

5. Western Palestine: Salfit, Tulkarem and Qalqilyah governorates

|

8. Negev: Ashkelon and regions** to the south east in the Negev and Eilat

|

9. Beersheba: Beersheba and Dead Sea regions

|

10. Ashdod: Ashdod and hinterland between the sea and Jerusalem City

11. Ramla: Ramla including southern parts of Petah Tiqwa

|

12. Eastern Metro.: Ramat Gan and environs within Tel Aviv District

|

13. Southern Metro.: Holon and environs within Tel Aviv District

|

20. Lower Galilee: Nazareth and Shefar’am regions

|

21. Upper Galilee Akko, Nahariyya, Karmiel, and north towards the Lebanese border

22. Eastern Galilee Zefat, Kinneret and Yizreel sub districts except Nazareth region

** here region refers to ‘natural regions’ as defined by the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics.

|

The threshold is the percentage of the votes cast required for a candidate to be elected. The proposed electoral districts were devised so that the number of elected representatives per district is consistently between 8 and 12, using as far as practicable existing Israeli and Palestinian administrative divisions. This means the threshold to get elected is between 8.33% and 12.5% by the single transferrable vote method of proportional representation, thus raising the threshold for election used currently in the Israeli election system. The exception would be Jerusalem with 18 elected representatives.

Territory

Governments

The three territories would each have its own unicameral assembly located

in Jerusalem. In the Israeli and West Bank territory

assemblies, the parties that could form a simple majority would form the

territory government. The leader of the

Government would be the Chief Minister and appoint a Territory Cabinet with ministerial

portfolios as per table 2 above. Chief

Ministers would automatically be members of the Commonwealth Executive Council (see below) to represent their Territory.

The Commonwealth Legislature

The Commonwealth Parliament would be

bicameral, with a Hebrew Chamber and an Arabic Chamber. The role of the Hebrew Chamber would be to

promote and protect Jewish aspirations, and the Arabic Chamber those of the

Palestinians and Arab Israelis. Legislation proposed by the Commonwealth

Executive Council (see below) would need the assent of both houses to be

passed. Thus, neither community could impose its will on the

other. If the two houses became deadlocked, a joint sitting with a two thirds

majority could override any veto. Each chamber would have a Speaker who

could act as spokesperson for their community’s interests, and have

parliamentary committees to study, review, scrutinize and propose amendments to

Executive Council legislation. While

segregating parliament along ethnic lines may seem at first unpalatable and run

counter to building unity, the advantages of this division are:

·

it offers a stronger voice for Israeli Arabs and West Bank Jewish

settlers who would be in minority populations within Israel and the West Bank

level;

·

most importantly, it removes the fears of both communities of being

outnumbered either now or in the future.

Candidates for

election would nominate for either the Hebrew or Arabic chamber of the

commonwealth parliament. For example, in

the Beersheba electorate all successful candidates, whether Jewish, Arabs or

Bedouin, would sit in the Knesset but if voters voted according to ethnicity, four

would be elected to the Hebrew Chamber and six to the Arabic chamber for their

commonwealth role. At the commonwealth

level, the numbers in each chamber would be 132 and 100 respectively, assuming

voters are in the same proportion as the general population. However, while mainstream voting would be

expected to largely follow such a pattern, smaller minorities such as Druze,

Bedouin and Arab Christians may be more variable in choosing which chamber

would be best for their interests.

The Commonwealth Executive

There would be no president or prime

minister of the Commonwealth; executive functions of government would be

fulfilled by the Commonwealth Executive Council of seven elected

representatives, appointed by a joint

sitting of both houses of the Commonwealth Parliament for a term of four years.

The Council would provide collective

leadership in areas of government

functions that cannot be retained by the territories. For example, a suggested model for the essential functional roles of the Executive Councilors could

be the following:

1. Presiding Officer of the Council, ceremonial head of state,

and Councilor for Jerusalem Administration

2. Deputy Presiding Officer,

Councilor for Population and Migration

3. Councilor for Defense

4. Foreign Affairs and Trade

Councilor

5. Councilor for Home

Affairs, Internal Security and the Commonwealth Police, and Gaza Special

Territory

6. Councilor for the

Economy, Transport, and Communications

7. Attorney General and

Councilor for Protection of Minorities

If voting for the Commonwealth Executive

Council would be by proportional representation of a joint sitting of both

houses and voting was along purely communal lines, then the number of Jewish Executive Councilors elected would be four,

and three would be Palestinians. Furthermore,

the Executive Council would inherently reflect the full spectrum of the parties

elected according to their voting strength in the parliament, so would always need

consensus decision making as no single bloc would ever achieve a majority. As well as ensuring both communities are

represented, so too would the left and right wings of party politics, secular

and religious, etc. Alternatively,

election to the Executive Council could require a two thirds majority, which

would tend to empower moderates acceptable to both communities and marginalize

extremists from both communities. To

function effectively, the Executive Councilors would need to take a bipartisan

approach, find shared interests and work

cooperatively. Executive

Councilors would no longer participate in parliamentary divisions, in order to

promote Council unity and solidarity and avoid schisms in the executive, and no

longer sit in their respective territory assemblies.

The Chief Ministers of Israel and the

West Bank would automatically be non-voting members of the Commonwealth

Executive Council without ministerial portfolio responsibilities.

The existing legal frameworks would

continue at territory level. There would

be two Supreme Courts, one for

Israeli legal matters and the other for Palestinian matters. Israeli law would

continue to apply in the Territory of Israel, and likewise Palestinian laws would apply in the

territory of West Bank. A new

Commonwealth High Court would be established to adjudicate on matters involving the Commonwealth government and inter-territory disputes. In the Capital

Territory of Jerusalem, initially Israeli laws would apply during a transition

to a Commonwealth legal system, but the lower courts in the territory would be directly

under the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth High Court. Seven High Court judges would be nominated by the Executive Council and confirmed by both

houses of parliament. At least three

places should be reserved for Jewish judges, and three for Palestinian judges.

Security

Recognizing the current existential

threat to Israel from terror groups and hostile states, responsibility for

defense of the Commonwealth would remain with the existing IDF initially. Over time if these threats to Israel’s

existence sufficiently diminish, the IDF

would become an integrated Commonwealth Defense Force. Until then, the IDF would have authority over

all external borders including the border with Gaza. The IDF would have no authority over internal

civilian movements, and IDF bases in the West Bank would be for purely

defensive purposes against external threats.

Israeli and Palestinian police forces

would continue to function separately within their respective territories. A bipartisan Commonwealth Police would be

responsible for security and policing in the Capital Territory and important designated

holy sites anywhere. These three police

forces would be responsible for internal security.

The intelligence services would be

under the authority of the Commonwealth Government, but during a transition period

the existing services would continue separately to report also to their

respective territory governments.

Rights to Free Movement, Employment and Residence

All 11.7 million ‘founding’

Palestinian and Israeli citizens resident at the time of formation of the

Jerusalem Commonwealth would be

entitled to free movement and employment throughout the Commonwealth.

Similarly, ‘founding’ citizens

would have the right to take residence anywhere in the Commonwealth. Founding Jewish citizens would have the right to live in the West

Bank territory and founding

Palestinian citizens would have the right to live in the Territory of Israel,

but new housing would be subject to territory approval.

Freedom of movement would be subject

to existing security checks and

controls, including where necessary separation barriers. However, the West Bank separation barrier

would have to be relocated from places that currently unduly disadvantage

Palestinian economic and family activities.

Citizens would be automatically allowed access to any area of the

Commonwealth, provided they pass the security checks deemed necessary by the

respective security services. The right

to access sensitive sites such as religious places of worship and holy sites

may be subject to extra controls.

Population and Migration

The right of return of Palestinian

refugees and the Law of Return for overseas Jewish populations would be broadly maintained, subject to negotiations of annual quotas between the Commonwealth

government and the territories. In principle, arrival of returning Palestinian refugees and

Jewish immigration would be done with a target

of maintaining the current demographic status quo. Territory Governments would be accorded

the right to determine which immigrants they accept, with the exception of the Capital

Territory of Jerusalem, where immigration intake would be directly determined

by the Commonwealth government.

Return of Palestinian refugees from outside the Commonwealth would be prioritized to those refugees who are

currently stateless (such as those in Lebanon and Syria),

contingent on those countries making peace with Israel.

To ensure new citizens have been well

integrated into the Commonwealth society, they would have a waiting period of

ten years before being accorded the right to the freedom of residence which

existing citizens of the commonwealth would have. For example, a

Palestinian refugee who has returned from Lebanon and been accepted to reside

in the West Bank with only four years of citizenship would not have the right

to reside in Israel unless that territory consented. The international community would need to

play its part by increasing third country resettlement, to avoid sudden population

strains within the Commonwealth.

Protection of

Minority Communities

Jewish communities living in the Territory of West Bank and Palestinian communities living in

the Territory of Israel would be

able to apply for minority status, on the

basis of security or significant cultural concerns.

Applications would be made by local government authorities to the

Commonwealth government, and

providing consent is provided by the relevant

territory, be accepted. If the territory government withholds consent,

adjudication would be by the Commonwealth High Court. Local governments

afforded minority status would have the right to civil protection. For

example, Jewish settlements in the

West Bank could apply to come under Israeli police protection. Minority

status would apply to local governments and not

individuals. For example, individual Jewish citizens wishing to take residence

in Hebron could not apply for

special police protection. Protection of minority communities could apply

automatically at the founding of the commonwealth, particularly to Jewish

settlements. Minority communities could also be exempted from territory

laws that are a significant challenge to that community’s culture. Territories

could thus develop cultural, religious and moral codes in keeping with the

majority’s wishes, but without infringing on minorities’ sensitivities, thus

avoiding internal ‘cultural wars’.

Integration

of Gaza into an Expanded Commonwealth

While the Gaza strip is in a sense an

independent city state already, the poverty, the collapsing infrastructure,

militancy and capacity to destabilize the commonwealth must be addressed as a

key element to founding the Commonwealth. Integration of the Gaza Special

Territory into the economy of the Commonwealth should begin as early as

possible, through privileged access to its economy through work visas, and

favorable customs and trade arrangements.

The international community would need to play a major role in providing

investment to boost the Gaza economy.

Residents of Gaza would elect their

own Assembly which would have a very large degree of autonomy, but its territory

borders would be maintained by the IDF. Subject

to security assessment, Gazans would have the right to free movement within the

Commonwealth, but not the right to reside, which would be at the discretion of

the Territory Governments. Gazans would

gain access to special passports issued by the Jerusalem Commonwealth to allow

international travel but would not have the right to vote in the Commonwealth

Parliament. The Gaza government would be

able to take disputed matters in its relations with Israel or the other

territories to the Commonwealth High Court.

Gaza could later join as the fourth

Territory of the Commonwealth, with a territory capital in Gaza City, and sending

40 elected representatives to Jerusalem, provided it met the following

conditions:

·

demonstrated de-weaponization

with independent checks and monitoring carried out by commonwealth security

forces;

·

recognition by

the Gaza Special Territory government of the rights of the Jewish people to a

homeland in Israel;

·

the Gaza

government would have to demonstrate free and fair election processes during

its period as an associated territory.

Economic incentives for Commonwealth

business to invest in Gaza should be developed, such as freedom from business

taxes and reduced goods and services taxes. Security measures to prevent

arms violations would be maintained by the IDF, until such time as they are no longer necessary, however

the naval blockade would end, and trade boycotts lifted at the earliest

opportunity.

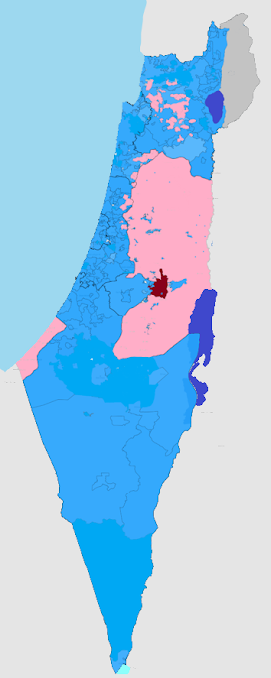

Expansion of the Commonwealth to

include Gaza Special Territory would increase the numbers of elected

representatives in the Arabic Chamber and influence the composition of the Commonwealth

Executive Council, but the veto power of the Hebrew Chamber would be unchanged,

and the balance of power in the Territory Assemblies of Israel, Jerusalem and

West Bank completely unaltered (see table 5).

In the long term, Gaza could be developed as an important free trade hub

in the eastern Mediterranean.

Income and corporate taxes would be collected by the Commonwealth

Government, while Goods and Services and Property taxes would be collected by

the territories. Reducing the existing

wealth disparity between Israelis and Palestinians will be a major challenge,

and while the tax and social welfare systems would play a role, the burden

should not fall wholly on the tax payers.

Reductions in security spending and wealth generation resulting from increased

economic activity would need to be managed to focus on providing equality of

opportunity as rapidly as possible across the territories. The Israeli Shekel would be re-branded as the

Jerusalem Shekel, one side of notes and coins in Hebrew the other in Arabic.

Census and Electoral Oversight

To avoid corrupt processes in both

population statistics and elections, it would be highly desirable that a single

bipartisan Bureau of Statistics and a single fully impartial and independent

electoral commission be formed, with the possibility of UN oversight or other

means of independent monitoring.

The electoral system would be overhauled

to make the elected representatives locally accountable to defined voters. Seventeen electoral districts each

electing 11 – 18 representatives would

be created based on current Israeli sub-districts and Palestinian governorates

(annex 3).

Flags

A new Jerusalem Commonwealth flag

would fly over commonwealth buildings and throughout the Capital Territory; the

Palestinian flag would fly throughout the West Bank Territory, and the Star of

David flag over Israel.

Conclusion

The strength of the proposed Jerusalem

Commonwealth is that the political system would be reconfigured to ensure power

sharing and cooperation at the commonwealth level while allowing self-determination

at territory level and does not rely on an improbable outbreak of goodwill or

self-sacrifice by either community. The

model promotes and empowers moderation and bipartisanship and marginalizes extremism.

Particular benefits to highlight are as follows:

For Israelis:

·

Increased Palestinian

support would be fostered for achieving peace deals with Arab and other

neighboring states, including to recognition of the right of the Jewish people

to their homeland in Israel.

·

Israel’s military

would maintain strong defense of the borders and current security checks and

barriers would be maintained as necessary, but the huge cost of security would

be expected to fall substantially.

·

Israelis would be

able to live anywhere in the Commonwealth, throughout Judea and Samaria, and

existing settlements would become legal, internationally recognized, and still protected

by Israeli security.

·

New economic

opportunities arise in the West Bank, and possibly the Gaza Strip.

·

Israeli law

maintained in the territory of Israel.

·

Jewish customs,

culture and right to self-determination throughout the Commonwealth, but

particularly in the Territory of Israel.

For Palestinians and other non-Jewish communities:

·

Citizenship for

all existing residents and over time, those who resettle from neighboring

countries, in an open democratic society where human rights are respected and

effective anti-corruption measures would be in place.

·

Access to

employment and residency throughout the Commonwealth.

·

Freedom of

movement and right to travel beyond the Commonwealths borders.

·

Palestinian law

maintained in the territory of West Bank.

·

Arab customs,

culture and right to self-determination throughout the Commonwealth, but

particularly in the West Bank Territory of Palestine.

·

An immediate

relief from the isolation in Gaza, and a pathway forward for greater

integration.

For both:

·

Jerusalem would

no longer be a symbol of division fought over as a shared capital city of the

two competing states in the two state solution, but rather a unifying

bipartisan city.

·

Freedom from fear

of domination by the other community.

·

The current

demographic balance is used to promote bipartisanship at the commonwealth level,

and this benefit is relatively impervious to demographic shifts in the future. The Jewish Law of Return and the rights of

Palestinian refugees would both be respected but with controls.

Achieving the Jerusalem Commonwealth would

need the election of candidates supporting the commonwealth in both the Israeli

Knesset and the Palestinian Legislative Council who could put into effect the

necessary constitutional changes. Both

legislatures would need to enact legal means to join together to form the first

bicameral Commonwealth Parliament and elect the first Executive Council that

would oversee the first elections and transition to the new structure. To achieve this requires either current

political movements to adopt the model as policy, or a new commonwealth

movement to be elected.

[1]

A directorial system of

government is when the executive power is equally divided among a select number

of individuals, ‘a directorate’, rather than a president or prime minister who

appoints the cabinet. Switzerland uses this form of government, where

directorates or executive councils govern all levels of administration, federal,

cantonal and municipal. It is a

system of government that reflects and represents the heterogeneity and

multiethnicity of the Swiss people. Israel's Parliamentary System, under which executive power is vested

directly in the Multi-person Cabinet, as opposed to the President acting on the

advice of the Cabinet in a normal Westminster System, can be seen as

semi-directorial.

Annex 2. Mapping current ministries of the Governments of Israel and Palestine to the model Commonwealth

Executive Council and Territory Governments

Commonwealth Executive Council

|

Current Israeli Ministries

|

Current Palestinian Ministries

|

Executive Council’s Office

|

Prime Minister's Office, Jerusalem and

Heritage

|

Prime Minister, Information, Jerusalem

Affairs

|

Population and Migration

|

Aliyah and Integration

|

|

Defense

|

Defense

|

|

Economy and Finance

|

Economy and Industry, Finance,

|

Finance

|

Energy, Transport and Communications

|

Communications, Energy, Transport and Road

Safety

|

Telecommunications and IT, Transport and

Communications,

|

Foreign Affairs and Trade

|

Foreign Affairs

|

Foreign Affairs and Expatriates

|

Home Affairs, Attorney General

|

Interior, Public Security

|

|

Territory Governments

|

||

Chief Minister’s Office

|

||

Agriculture, Environment and Water

|

Agriculture and Rural Development,

Environmental Protection

|

Agriculture

|

Planning, Housing

|

Construction and Housing

|

Public Works and Housing

|

Health and Sports

|

Health, Sports

|

Health

|

Education and Research, Culture

|

Education, Culture, Science and Technology

|

Education, Higher Education and Scientific

Research, Culture

|

Employment, Transport

|

Labor,

|

Labor, Local Govt.

|

Justice

|

Justice

|

Justice

|

Social Services,

|

Social Equality, Social Affairs and Social

Services

|

Social Development, Women’s Affairs

|

Tourism, Culture and Religious Services

|

Tourism, Culture and Religious Services

|

Tourism and Antiquities

|

Development of the Negev and the Galilee

|

AFTERWORD:

AFTERWORD:

Other federal models can be found at:

The four models at a glance:

|

Model

|

FM

|

IPF/HLU

|

IPC

|

JC (this

model)

|

|

Citizenship

|

Israeli only

|

Both

|

Both

|

Commonwealth only

|

|

one or two

states?

|

one – Israel, but 30 cantons

|

two, defined by people not territory

|

two confederated nation states

|

one, but with many powers devolved to territory governments

|

|

Head of

State

|

Israeli president

|

Federal president

|

Three presidents: Israel, Palestine, Confederation

|

Presiding member of the Executive Council

|

|

Head of Govt

|

Israeli PM

|

Federal PM

|

Three PMs: Israel, Palestine, Confederation

|

7-person bipartisan executive council

|

|

Parliament

|

Knesset with added upper house

|

Federal and two national parliaments

|

Federal and two national parliaments

|

One national parliament with Hebrew and Arabic chambers

|

|

National

elections

|

Israeli system

|

System not stated but 4 year terms

|

300 districts across confederation, electoral system not specified

|

proportional representation in 22 electoral districts, 4 yr terms

|

|

Power

sharing

|

Majority rules

|

President / PM must be from opposite ethnic

|

President / PM opposite ethnicity, with 2 yearly rotation

|

Bipartisan commonwealth parliament and executive

|

|

Veto power

|

none

|

not stated

|

55% of either Israeli or Palestinian MPs

|

51% of either Hebrew or Arabic chamber MPs

|

|

Sub-national

govt

|

20 Jewish Cantons, 10 Palestinian

|

Israeli (1), Palestinian (3), and six Federal areas

|

No – Israel and Palestine are separate nations

|

Israel, West Bank, Jerusalem territories +/- Gaza

|

|

Gaza

|

excluded

|

included

|

included

|

inclusion possible

|

|

Golan

|

included

|

not included (?)

|

included

|

inclusion possible

|

|

Jerusalem

|

Israeli capital

|

1 of 6 federal districts

|

not addressed

|

Commonwealth capital, capital of Israel & WB

|

|

WB Settlement

|

separate cantons

|

federal districts

|

not addressed

|

Integrated into West Bank with protections

|

|

Overall

summary

|

Israeli system of govt with semi autonomous cantons added

|

Supranational federation over two non-territorial ‘nations’

|

Confederation of two separate nations

|

Inherently bipartisan Federal state, with structures similar to Switzerland

and Belgium

|

Comments

Post a Comment