One State: A Joint Government for Israel-Palestine

A One State Solution: The Joint Territories of Israel-Palestine

A model of governance that would promote bipartisan cooperation and self-determination

While the official position of Israel,

Palestine and the international community is that a two state solution is the best

way to resolve the conflict, history shows it has either been unachievable or

the parties are unwilling to find mutually acceptable ways to achieve it.

The alternative is a one state, usually

federal, solution that has won little support so far, as the Jewish community

fears being outnumbered or a dilution of the Jewish nature of their territory, and

the Palestinian community do not want to surrender their long battle for

nationhood. Extremists on both sides

also promote a one state takeover of all the land, with expulsion of the other

community.

This paper proposes an approach to the

one state solution that preserves the autonomy of the two main communities as

far as possible through separate territory governments, while in areas of

nationhood, the three parts of government, legislative, executive and judiciary

would be inherently bipartisan and structured to ensure consensus decision

making.

The aim is to replace the current

military and sometimes violent sectarian conflict with a political system for

sustained conflict resolution and negotiation in a bipartisan joint government

structured to promote cooperation and pursuing shared interests and mutual

benefits.

While most democracies have a

governing party or coalition and an opposition, this adversarial majority-rules governance is counter-productive in the

context of forming a joint government between Israel and Palestine.

There are three unique features of

this model compared to the many other federation and one state models that

exist:

1.

replacing the

offices of President and Prime Minister with a Swiss-style pluralistic 7-person Executive Council thus avoiding the difficult

issue of balancing the ethnicity of the Heads of State and Government;

2.

separation of the

two main communities’ elected representatives into two chambers of a Joint Assembly, giving both communities the same

power to accept or reject legislation, and rather than hindering understanding

between Jews and Palestinians, provide a forum for structured meaningful

dialogue for which the elected representatives would be wholly accountable at

the ballot box;

3.

the inter-linking of the territory assemblies

and the Joint Assembly through common

membership by representatives elected uniformly across all territories,

thus promoting a unity of purpose and neutralizing the risk of conflicts

between territories and the Joint Government.

Joint Territories

of Israel - Palestine

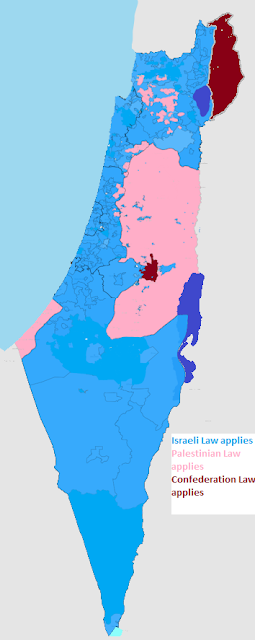

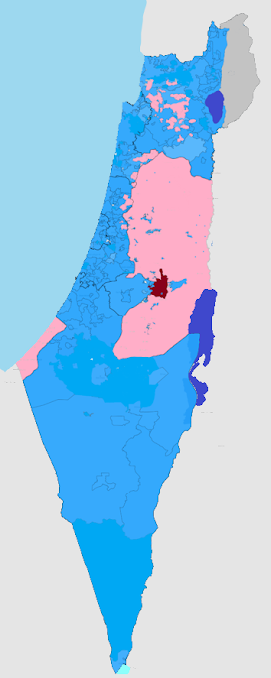

Constituent territories would be based

on the 1967 borders as follows:

- the Territory of Israel, a homeland for the

Jewish people, with West Jerusalem ceded to a newly created Capital Territory;

- the Palestinian Territory of West

Bank, or aḍ-Ḍiffah l-Ġarbiyyah, a homeland for the Palestinian people, with

East Jerusalem ceded to the Capital Territory;

- the shared Capital Territory of

Jerusalem, which would be home to the Knesset, the Palestinian Legislative

Council, as well as newly created Capital Territory and Joint Assemblies, under

the jurisdiction of both peoples through a bipartisan Joint Government;

- the Special Palestinian Territory of

Gaza could be included as a constituent territory after a period of economic

development, disarmament and willingness to accept Israel as a Jewish homeland.

Under international law Golan could no

longer be included as part of the Territory of Israel; however, as an

interim measure Golan

would become a Joint Government

administered district until a sustained peaceful solution with Syria and

Lebanon is found.

The territories would maintain

sovereignty over their internal borders and could negotiate internal land swaps

if mutually agreeable. However, only the

Joint Government would have the power to negotiate land swaps with Egypt,

Jordan, Lebanon or Syria but such swaps would be subject to the approval of the

relevant Territory government.

Citizenship

All current Israeli citizens, long term residents

of Israel and the West Bank, and Palestinian refugees residing in

the West Bank would automatically become ‘founding’ citizens of Israel -

Palestine. Future rights to citizenship for Gazan Palestinians

and new immigrants would be granted as set out below. All citizens would have access to Israel-Palestine

passports, but could self identify as Israeli or Palestinian according to

preference, much as citizens of the UK variously identify as English, Scottish,

Welsh or Irish. In this proposal, the

term Palestinian will be taken to include Arab Israelis, Druze and Bedouins.

Population of Israel

- Palestine

The estimated populations of the proposed territories of Israel –

Palestine in 2020 are in table 1 below.

JEWISH

(%)

|

PALESTINIAN (%)

|

TOTAL

|

|||

ISRAEL

|

5,688,400

|

(74.9)

|

1,900,200

|

(25.1)

|

7,588,600

|

PALESTINIAN

WEST BANK

|

427,200

|

(13.4)

|

2,755,200

|

(86.6)

|

3,182,400

|

JERUSALEM

|

555,800

|

(60.6)

|

363,600

|

(39.4)

|

919,400

|

ISRAEL – PALESTINE

|

6,671,400

|

(56.9)

|

5,019,000

|

(43.1)

|

11,690,400

|

GOLAN

|

23,600

|

(46.7)

|

27,000

|

(53.3)

|

|

GAZA

PALESTINE

|

0

|

0

|

2,048,000

|

(100)

|

2,048,000

|

EXPANDED

ISRAEL-PALESTINE

|

6,695,000

|

(48.6)

|

7,094,000

|

(51.4)

|

13,789,000

|

The population estimates are based on latest

official estimates as at 31 December 2018 from the Central Bureau

of Statistics of Israel and

2020 projection from the Palestinian Bureau of Statistics released on 6 March 2020 as found at https://www.citypopulation.de/Asia.html on 8 June 2020.

Division of

Power between the Territory and Joint Governments

As far as possible, the functions of Government would remain mostly in

the domain of the territories, but certain powers would need to be ceded to the

Joint Government as shown in table 2.

Table 2: areas of responsibility

for Territory governments and the Joint Government

Territory

Governments

|

Joint

Government

|

Health,

Sport and Recreation

|

Defense

|

Education

and Research

|

Internal

Security and Justice

|

Social

Services, Child Care

|

Foreign

Affairs and Trade

|

Environment,

Water, Antiquities and Tourism

|

Immigration

and Citizenship

|

Planning,

Housing, Local Government

|

Taxation and

Economic policy

|

Territory

Law and Justice, Prisons

|

League Law

(Attorney General)

|

Employment, Local

Transport, Road and Rail

|

Air transport,

Ports, Communication

|

Electoral

Reform and Elected Representatives

The semi-defunct electoral system of Palestinians and the recent evidence

of a political impasse in the Israeli Knesset may be both a cause and a symptom

of failure in the protracted search for a resolution to the conflict. Aligning, reforming and revitalizing the

electoral systems would be essential.

An all-territories election would be held every four years to choose

parliamentary representatives, who would be

elected by proportional representation with one representative per 32,500 voters,

to ensure all votes are of equal value. Compulsory

voting by all adult citizens over the age of 18 would ensure equality of

representation across the territories. Nineteen multi-member electoral districts would be created so

that elected representatives would be more directly accountable at a local

level to the voters in their respective districts (annex 2), with the electorates

based on

existing Israeli sub-districts and Palestinian governorates. The threshold for election would be a minimum 5.88% of

votes cast by the single transferrable vote method of proportional

representation, higher than the threshold for election used currently in the

Israeli election system.

Elected representatives would have dual responsibilities. They would represent their electorates in

their respective territory assemblies and represent their community according

to their preference in the Joint Assembly.

Territory Assemblies

The three constituent territories would each have its own unicameral

assembly, all located in Jerusalem. Based on the current populations and estimated

number of voters, the Israeli Knesset would have 160 representatives, the West

Bank Legislative Council 55, and a new assembly in Jerusalem 17, for a total of

232 elected representatives. Although

Jewish citizens make up 56% of the population, they would make 64% of voters,

as a higher proportion of the Jewish population is aged 18 or over.

Territory

Executives

In the Israeli and West Bank territory

assemblies, the party or parties that could form a simple majority would form

the territory government. The leader of

the Government would be the Chief Minister and appoint a Territory Cabinet with

ministerial portfolios as per table 2 above.

In the Capital Territory, an Administrator

would be appointed by the Joint Government who along with appointed assistant

administrators would fulfil the executive functions of government for the Capital. The Capital Territory assembly would have the

power to sack the appointed administration and accept or reject local laws and

measures proposed by the Administration.

This arrangement aims to ensure Jerusalem functions as a bipartisan

national capital, with government accountable to both Palestinians and

Israelis, a unifying influence, while ensuring local voters’ concerns are not

disenfranchised.

The Joint Assembly

The Joint Assembly would be bicameral,

with a Hebrew Chamber and an Arabic Chamber.

The role of the Hebrew Chamber would be to promote and protect Jewish

aspirations, and the Arabic Chamber those of the Palestinians and Arab

Israelis. Legislation proposed by the Joint Executive Council (see below) would

need the assent of both chambers to be passed. Thus, neither community

could impose its will on the other. Each chamber would have a Speaker who could act as

spokesperson for their community’s interests, and have parliamentary committees

to study, review, scrutinize and propose amendments to Executive Council

legislation.

Candidates for

election would nominate for either the Hebrew or Arabic chamber of the Joint

Assembly. For example, in the Beersheba

electorate all successful candidates, whether Jewish, Arabs or Bedouin, would

sit in the Knesset but if voters voted according to ethnicity, ten would be

elected to the Hebrew Chamber and four to the Arabic chamber in the Joint

Assembly. The estimated number of

representatives nationally in each chamber would be 149 and 83 respectively,

assuming voters choose candidates of their own community. However, while mainstream voting would be

expected to largely follow such a pattern, smaller minorities such as Druze,

Bedouin and Arab Christians may be more variable in choosing which chamber would

be best for their interests.

While

segregating the legislature along ethnic lines may seem at first distasteful,

even racist, and run counter to building unity, the advantages of this division

are:

·

a stronger voice for Israeli Arabs and West Bank Jewish elected

representatives who would be in a minority in their respective territory

assemblies;

·

it reflects the purpose of the Joint Assembly, to structure dialogue

between the divided population groups, and ensures the majority view of each

community is clearly and democratically expressed with accountability to voters

– in some sense, the representatives in the two chambers would be negotiators

and advocates for their communities as challenges arise, but represent much

more broadly the political spectrum within each community, rather than the

current narrower negotiation (or lack thereof) by two governments dominated by

one political stream of thought;

·

most importantly, it removes the fears of both communities of being

outnumbered either now or in the future, as numerical strength does not affect

the power of each chamber to accept or reject legislation;

·

conversely, a single chamber with for example 149 Jewish and 83

Palestinian members would mean the latter can always be outvoted, or on

occasion a minority view within either community could prevail if the other

community could be persuaded to support the minority view.

The Joint Executive Council

There would be no president or prime

minister of Israel-Palestine; executive functions of government would be shared

equally by the seven members of the Joint Executive Council, elected

representatives appointed by a joint sitting of both houses of the Joint

Assembly for a term of four years. The

Council would provide collective leadership in areas of government functions that cannot be retained by the territories.

For example, a suggested model for the essential functional roles of the Executive Councilors could be the

following:

1. First Councilor, Presiding Officer of the Council, and Councilor for Jerusalem and

Golan Admin.

2. Councilor for Population

and Migration

3. Councilor for Defense

4.

Foreign Affairs and Trade Councilor

5. Councilor for Home Affairs, Internal Security,

and Gaza Special Territory

6. Councilor for the Economy, Transport, and Communications

7. Attorney General and Councilor for Protection

of Minorities

The Presiding Officer’s role would be to chair Executive

Council meetings and conduct ceremonial and diplomatic Head of State

functions. The presiding officer would not

have presidential powers, such as allocation of Executive Council portfolios,

which would instead be chosen by consensus or by voting within the council. A system of rotation of the position every

one or two years based on seniority or by voting would promote a bipartisan and

pluralist fulfilment of the position.

If voting for the Joint Executive

Council were by proportional representation of a joint sitting of both houses

and voting was along purely communal lines,

then the number of Jewish Executive Councilors elected would be four or five,

and two or three would be Palestinians.

Furthermore, the Executive Council would reflect the full spectrum of

the parties elected according to their voting strength in the Joint Assembly,

so would always need consensus decision making as no single bloc would ever

achieve a majority. As well as ensuring

both communities are represented, so too would the left and right wings of

party politics, secular and religious, etc.

To function effectively and achieve outcomes, the Executive Councilors

would need to take a bipartisan approach, find shared interests and work cooperatively, as the veto

power of the assembly would side-line partisan proposals. Executive Councilors would no longer vote in

legislative divisions, in order to promote Council unity and solidarity and

avoid schisms within the executive, and no longer sit in their respective territory

assemblies.

The Chief Ministers of Israel and the

West Bank would automatically be non-voting members of the Joint Executive

Council but without ministerial portfolio responsibilities.

This model is a unique solution to a

central problem with most other one state models, where the issue of choosing a

Prime Minister or President raises questions of whether Jewish Israelis are

willing to accept an Arab Prime Minister and vice versa for the Palestinians.

The existing legal frameworks would

continue at territory level. There would

be two Supreme Courts, one for

Israeli legal matters and the other for Palestinian matters. Israeli law would

continue to apply in the Territory of Israel, and likewise Palestinian laws would apply in the

Territory of West Bank. A new High

Court of Israel – Palestine would be established to adjudicate on matters involving the Joint

Government and inter-territory disputes. In the Capital Territory

of Jerusalem, initially Israeli laws would apply during a transition to an

Israel - Palestine legal system, but the lower courts in the Capital territory

would be directly under the jurisdiction of the High Court. Seven High Court judges would be nominated by the Executive Council and confirmed by both

chambers of the Joint Assembly. At least

three places should be reserved for Jewish judges, and three for Palestinian judges.

Inclusion

of Gaza into the Joint Government

While the Gaza strip is in a sense an

independent city territory already, the poverty, the collapsing infrastructure,

militancy and the capacity to destabilize Israel-Palestine would need to be

addressed as a key element to the Joint Territory’s foundation. Integration

of the Gaza Special Territory into the economy of Israel-Palestine should begin

as early as possible, through privileged access to work visas, and favorable

customs and trade arrangements.

Residents of Gaza would elect their

own Legislative Council located in Gaza City which would be autonomous, buts

its members would not be eligible to sit in the Joint Assembly. The IDF would continue to have control over its

borders. Gazan Palestinians would be

able to apply to travel and work within Israel-Palestine subject to security

assessments, but residential rights would be at the discretion of the Territory

Governments. Gazans would be able to

apply for Israel-Palestine passports to allow international travel. Gazan Palestinians would have access to the

High Court system for matters concerning the exercise of these privileges and rights.

Gaza could join as a constituent territory

of Israel-Palestine, with its Legislative Council relocated to Jerusalem, and sending

33 elected representatives to the Joint Assembly, who would automatically be eligible

to stand for the Joint Executive Council.

The following conditions would need to be met:

·

demonstrated disarmament

with independent checks carried out by security forces;

·

recognition by

the Gaza Special Territory government of Israel as the Jewish people’s homeland;

·

demonstration of the

ability to hold free and fair elections.

Expansion of Israel-Palestine to

include Gaza Special Territory would increase the numbers of elected

representatives in the Arabic Chamber and influence the composition of the Joint

Executive Council, but the veto power of the Hebrew Chamber would be unchanged,

and the balance of power in the territory assemblies of Israel, Jerusalem and

West Bank completely unaltered (see table 4).

Interestingly, even though in this expanded Israel-Palestine the

Palestinian population is in a majority, based on estimates of voter numbers,

the Jewish community would form a slightly larger electorate, as the

Palestinian population includes a higher proportion of citizens below voting

age. In this scenario, the Executive

Council would be likely to consist of four Jewish and three Palestinian

councilors each.

Inclusion

of Golan

Under international law Golan could no

longer be included as part of the Territory of Israel; however, as an

interim measure Golan

would become a Joint Government

administered district until a sustained peaceful solution with Syria and

Lebanon is found. Until its status is resolved,

Golan voters would elect two representatives to sit in the Joint Assembly, with

Golan split into two single member electorates, one in North Golan / Mt Hermon

the other in South Golan. The former

would likely return a Druze elected representative, the latter a Jewish

representative. Golan would be

administered directly by the Joint Government.

Its final status could be determined by a plebiscite after a

fixed period of at least 10 years of peace.

Table 4: population and elected

representatives by territory and community (estimated)

Security

Because of the paramount importance of

security in Israel-Palestine, a Joint Security and Emergency Council would be

mandated with special powers and arrangements to empower the Chief Ministers

when there is a specific threat to their respective territories. Members of the Council

would include in addition to the Chief Ministers, the First Councilor, the Councilors for Defense, Internal Security and Foreign

Affairs. Chief Ministers would have the

power to veto decisions affecting their particular territory.

Recognizing the current existential

threat to Israel from terror groups and hostile states, responsibility for

defense of Israel-Palestine would remain with the IDF and Palestinian National

Security Force, under the command of the Joint Executive Council. When the situation becomes safer, an integrated Joint Defense Force would be developed.

Israeli and Palestinian police forces

would continue to function separately within their respective territories. A bipartisan Joint Police would be

responsible for security and policing in the Capital Territory, the Golan and

important designated holy sites anywhere.

Equal Rights to Free Movement, Employment and Residence

All citizens at the time of foundation

of Israel-Palestine would have the

right to freedom of movement and employment throughout the territories, as well

as the right to take residence anywhere. However, new housing would be subject to territory

approval. Thus, existing Jewish

settlements could remain, and West Bank Palestinian refugees’ rights to live in

Israel would be guaranteed. New citizens

would have the right to movement and employment, but free residential rights

would require a period of ten years citizenship to qualify.

Population and Migration

The right of return of Palestinian

refugees and the Law of Return for overseas Jewish populations would be broadly maintained, subject to negotiations of annual quotas between the Joint Government

and the territories. In principle, arrival of returning Palestinian refugees and

Jewish immigration would be done with a target

of maintaining the current demographic status quo.

Protection of

Minority Communities

Local government areas containing Jewish

communities in the West Bank and Palestinian communities in Israel would be able to apply for minority status, on the

basis of security or significant

cultural concerns.

Applications would be made

by local government authorities to the Joint Government, and providing consent is provided by the relevant territory, be accepted. If the territory

government withholds consent, adjudication would be by the High Court.

Local governments afforded minority status would have the

right to request civil protection. Individual citizens would not be able to apply

for minority status in this sense.

The Israeli Shekel would be rebranded as the Israel-Palestine Shekel, one

side of notes and coins in Hebrew the other in Arabic.

Language

Hebrew and Arabic would be the official languages of all territories, and

laws would be required to be made in both.

Conclusion

If this model is implemented:

·

Israel would be recognized by the

Palestinians and Arab world as a Jewish Homeland.

·

Palestinians gain self-government and

citizenship, and their democracy would be revitalized.

·

Jerusalem would be the undivided capital of

both Israel and Palestine, jointly managed.

·

West Bank Jewish settlements could remain,

and Palestinian refugees could live in Israel, subject to controls.

·

Gaza embargo relieved, and the path to

citizenship becomes clear.

·

Golan’s status will be resolved, contingent

on a peace process with neighboring countries.

·

The Joint Government would be inherently

bipartisan, while the Israeli Government would continue to reflect the will of

the Jewish majority, and the Palestinian assembly or assemblies would reflect

the will of the Palestinian people.

-

Annex 1: Schematic representation

of the interlinked assemblies of Israel-Palestine

Annex 2: Example of possible multi-member

electoral districts.

The table is for illustrative purposes only of how the electoral system

might operate. The Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics provides age data

according to three categories of Population Groups: Jews, Arabs including Arab

Christians and Druze, and Others defines as Non-Arab Christians,

members of other religions, and those not classified by religion in the

Population Register. Most of the

‘Others’ are non-Jewish family members of Jewish immigrants to Israel, and

therefore included for this electoral example with the Jewish population

group. The overall number of voters is

likely overestimated, as data on non-citizens is not readily available, so some

non-citizens without eligibility to vote may be included in these data.

Estimated number of voters (000)

|

# to be elected

|

est. Jewish /

Others

|

est. Arabs

|

threshold

%

|

||

1. Hebron

|

411.9

|

13

|

1

|

12

|

7.69

|

|

2. Jerusalem

Hills / Jericho

|

331.6

|

10

|

2

|

8

|

10.00

|

|

3. Ramallah

/ Salfit

|

362.4

|

11

|

3

|

8

|

9.09

|

|

4. Nablus / Tubas

|

282.8

|

9

|

0

|

9

|

11.11

|

|

5. Northern

West Bank

|

397.5

|

12

|

0

|

12

|

8.33

|

|

West Bank LC TOTAL

|

|

55

|

6

|

49

|

|

|

6. Jerusalem City

|

544.0

|

17

|

12

|

5

|

5.88

|

|

Capital Assembly TOTAL

|

|

17

|

12

|

5

|

|

|

7. Northern

Israel

|

505.3

|

16

|

9

|

7

|

6.25

|

|

8. Akko Sub

District (S.D.)

|

435.4

|

13

|

5

|

8

|

7.69

|

|

9. Haifa

S.D.

|

439.8

|

14

|

12

|

2

|

7.14

|

|

10. Hadera

S.D.

|

297.2

|

9

|

5

|

4

|

11.11

|

|

11. Sharon

S.D.

|

328.6

|

10

|

8

|

2

|

10.00

|

|

12. Petah

Tiqwa S.D.

|

514.1

|

16

|

15

|

1

|

6.25

|

|

13. Ramla

Bet Shemesh

|

363.7

|

11

|

10

|

1

|

9.09

|

|

14. Rehovot

S.D.

|

433.7

|

13

|

13

|

0

|

7.69

|

|

15. Tel Aviv

Region**

|

436.2

|

13

|

13

|

0

|

7.69

|

|

16. Ramat

Gan Region

|

363.5

|

11

|

11

|

0

|

9.09

|

|

17. Holon

Region

|

246.8

|

8

|

8

|

0

|

12.50

|

|

18. Ashqelon

S.D.

|

379.4

|

12

|

12

|

0

|

8.33

|

|

19. Beersheva

S.D.

|

462.7

|

14

|

10

|

4

|

7.14

|

|

Israel Knesset TOTAL

|

|

160

|

131

|

29

|

|

|

Joint Assembly TOTAL

|

|

232

|

149 Hebrew

|

83 Arabic

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jerusalem Hills / Jericho:

|

Bethlehem, Al-Quds (excluding East Jerusalem) and Jericho

governorates

|

|||||

Northern West Bank:

|

Jenin, Qalqilyah and Tulkarm governorates

|

|||||

Northern Israel:

|

Zefat, Kinneret, and Yizreel sub-districts

|

|||||

Ramla Bet Shemesh

|

Ramla sub-district and Jerusalem district excluding City of

Jerusalem

|

|||||

|

|

** region refers to natural region as defined by Israel’s CBS

|

|||||

Annex 3: Mock Election

for the Joint Executive Council (JEC) and Territory Executive Cabinets

The following material is an example of how a future

Israel-Palestine election could play out.

Fictitious party names are simply for illustrative purposes. The mock election starts at the joint sitting

of both chambers of the Joint Assembly after the general election results are

final. Successful parties in the all-territories

general election are as follows:

·

Social Democratic Party, the only party to field

both Hebrew and Arabic candidates

·

Torah Shas Party, whose base is mostly

conservative religious Jews

·

New Likud Party, a conservative secular party favored

by business sector

·

Jewish Left Party, favored by Russian Jewish

immigrants, progressives, academics and young voters

·

Al’Aqsa Party, whose base is a mix of nationalist

and socially conservative Moslems

·

New

Fatah Party, a broad based centrist party, the successor to the

Palestinian National Authority

·

Minor parties: Bedouin Party, Druze Party,

Settlers Party

Joint Assembly voting for Executive Council

The single transferable vote method of proportional representation

could be used, as in the general election.

Quota for

election to the executive council would be 29 votes – calculated by number of

votes divided by the <number of quotas to be filled plus 1> = 232 / (7 +

1) is 29

Votes are

allocated to the top candidate of each party in each round until all quotas are

filled. When 29 votes are reached by a

candidate, those 29 votes are ‘expended’ but ‘surplus’ votes may be transferred

in the next round, until all seven positions are filled. Different counting systems can be used,

including calculating mathematical fractions based on a ballot indicating preferences. In this example, simpler to understand iterative

rounds are used.

Joint Sitting of both chambers

First round:

·

The Social Democratic party is the biggest

party, with 55 elected to the Hebrew Chamber and 17 to the Arabic chamber:

combined vote at joint sitting is 72 – enough to attain two quotas (58

votes). Twelve Hebrew representatives

vote for their Arabic colleague to ensure she gains a quota. Thus two social democrats are elected to the

JEC, Rachel Leberstein from Tel Aviv and Hanan Samaan from Ramallah.

·

Torah Shas has 43 seats, enough to elect one

councilor, Simeon Meir from Jerusalem.

·

New Fatah has 44 seats, enough to elect one

councilor, Mahommad Mansour from Nablus.

Second round. As no other party has a quota, a second round

of voting for the three remaining positions is held. The three small parties do not propose

candidates, but all the other parties do.

The Druze and Bedouin Parties vote for the second New Fatah candidate,

while the Settler Party backs the second Torah Shas candidate. No party reaches a quota.

Round 3. The New Fatah’s next candidate is eliminated

and the party transfers its 11 votes to the Al’Aqsa Party candidate, thus

reaching a quota for Jalaa Suleiman from Hebron.

Round 4. The next Al’Aqsa candidate is eliminated,

with 7 of its remaining votes going to the Social Democrat candidate but in a

surprise move, one vote goes to the New Likud candidate, Yuditha Cohen from

Haifa thus giving her a quota.

Round 5. Torah Shas candidate is eliminated, and 12 of

its remaining 18 votes transfer to the Jewish Left party candidate, Boris

Trotskiev, from Rishon LeZiyyon who thus gains the final place on the Council.

ASSEMBLY

|

Hebrew

Representatives

|

Arabic

Representatives

|

|||||||||

Soc. Dem.

|

Torah Shas

|

New Likud

|

Jew Left

|

Settler

|

Soc. Dem.

|

Al’Aqsa Party

|

New Fatah

|

Bed-ouin

|

Druze

|

Total

|

|

Election

night results

|

|||||||||||

Knesset

|

52

|

33

|

26

|

18

|

2

|

9

|

10

|

6

|

2

|

2

|

160

|

Jerusalem

|

3

|

6

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

17

|

|||

WBLC

|

3

|

1

|

2

|

6

|

15

|

28

|

55

|

||||

Joint

|

55

|

42

|

28

|

20

|

4

|

17

|

26

|

36

|

2

|

2

|

232

|

Joint

sitting to elect Executive Council

|

|||||||||||

transfers

|

-12

|

+12

|

|||||||||

round 1

|

43

|

42

|

28

|

20

|

4

|

29

|

26

|

36

|

2

|

2

|

|

4 quotas

|

(29)

|

(29)

|

(29)

|

(29)

|

|||||||

balance

|

14

|

13

|

28

|

20

|

4

|

26

|

7

|

2

|

2

|

||

transfers

|

4

|

4

|

|||||||||

round 2

|

14

|

17

|

28

|

20

|

26

|

11

|

|||||

transfers

|

11

|

||||||||||

round 3

|

14

|

17

|

28

|

20

|

37

|

||||||

1 quota

|

(29)

|

||||||||||

balance

|

14

|

17

|

28

|

20

|

8

|

||||||

transfers

|

7

|

1

|

|||||||||

round 4

|

21

|

17

|

29

|

20

|

|||||||

1 quota

|

(29)

|

||||||||||

balance

|

21

|

17

|

0

|

20

|

|||||||

transfers

|

2

|

15

|

|||||||||

round 5

|

23

|

35

|

|||||||||

1 quota

|

(29)

|

||||||||||

Joint Executive Council composition is therefore:

Two Social

Democrats (one Hebrew, one Arabic), one Torah Shas, one Al’Aqsa, one New Fatah,

one New Likud and one Jewish Left. Rachel

Leberstein is elected unopposed as Presiding Officer. Using her considerable negotiating skills, all

portfolios are assigned without a vote, as follows:

1.

Rachel Leberstein, Presiding Officer, and

Councilor for Jerusalem and Golan Administration

2.

Hanan Samaan, Councilor for Defense

3.

Boris Trotskiev, Population and Migration

4.

Mahommad Mansour, Foreign Affairs and Trade

5. Yuditha

Cohen, Councilor for the Economy,

Transport, and Communications

6. Simeon

Meir, Councilor for Home Affairs, Internal

Security, and Gaza Special Territory

7.

Jalaa Suleiman, Attorney

General and Councilor for Protection of Minorities

As Executive

Councilors no longer participate in parliamentary divisions, the status of the Joint

Assembly would become:

·

Hebrew Chamber:

Social Democrats - 54, Torah Shas - 41, New Likud - 27, Jewish Left - 19,

and Settlers – 4

·

Arabic Chamber:

New Fatah – 35, Al’Aqsa – 25, Social Democrats - 16, Bedouin – 2, and Druze – 2

·

One can see that the mix of political parties

would not necessarily split along communal lines, and that alliances between

Arabic and Hebrew members are very likely on certain issues.

Territory Assemblies confirm Chief Minister

Once the Joint Executive Council membership has been

decided, all remaining 225 elected representatives then split into their

respective territory assemblies to formally endorse their Chief Ministers and governments.

Israel: in the Knesset, 79 seats

required to form a majority, (157 elected representatives remain, excluding the

three Israeli based Executive Councilors)

·

the Social Democrats and the Jewish Left parties

with 58 and 17 remaining elected representatives respectively form a coalition;

New Fatah and the Bedouin and Druze parties all pledge their support, without

joining the coalition.

·

the Social Democrat party leader becomes Chief

Minister and appoints her Cabinet Ministers

West Bank: in the Legislative Council 27

seats required to form a majority (52 seats excluding 3 West Bank based Executive

Councilors)

·

New Fatah has a clean sweep with 27 out of 52

seats, and the party leader becomes Chief Minister and appoints his Cabinet

Ministers

Jerusalem: The

Joint Executive Council proposes a General Secretary who coordinates the

various territory departments such as health, education, territory public transport,

and so on. Chief Administrator and

assistant administrators based on technical rather than political

considerations, to run the Capital Territory’s health, education, transport,

social welfare systems. The elected

representatives formulate policy and regulations to manager no majority

required to form government, as territory administration will be appointed by Joint

Government.

The Chief Ministers of Israel and the West Bank attend JEC

meetings as non-voting members of the Joint Executive Council.

Comments

Post a Comment